By Francesc Borrull · November 3, 2025

To Rossella and Elisabetta

I. Canzone per Silvia: An Italian in America

Every story of injustice has two sides: one that gets told, and another that gets lost in translation. When I finished watching Hulu’s The Twisted Tale of Amanda Knox, my mind immediately traveled to a song I first discovered years ago: Canzone per Silvia by Francesco Guccini. The story told in Guccini’s haunting ballad is, in a way, the reverse mirror of Amanda Knox’s.

Amanda was an American in Italy, accused of a murder she didn’t commit. Silvia, Guccini’s Silvia Baraldini, was an Italian in America—also imprisoned, also misunderstood, also made a symbol of something far greater than her own humanity. Guccini, with his trademark moral clarity, captured that paradox in verse:

“Già, l’America è grandiosa ed è potente, tutto e niente, il bene e il male…”

Yes, America is grand and powerful, everything and nothing, good and evil…

and later,

“Perché non è possibile rinchiudere le idee in una galera.”

Because it is not possible to lock ideas inside a prison.

Silvia’s crime was political. Amanda’s was circumstantial. But in both cases, we see how nations project their fears onto individuals. I have been to Italy several times—walked through the piazzas, shared meals with friends who became family, picked up enough Italian to understand the beauty and nuance of Guccini’s lyrics. There’s a Mediterranean familiarity that feels close to home for me, maybe because, as I learned through a DNA test, I am seven percent Italian. That number might be small, but it feels significant. I understand that culture not as a tourist, but as someone whose roots—Catalan, Mediterranean, European—share its warmth and contradictions. Guccini’s song is a lament and a warning: justice is fragile, and when it becomes political or symbolic, it ceases to be just.

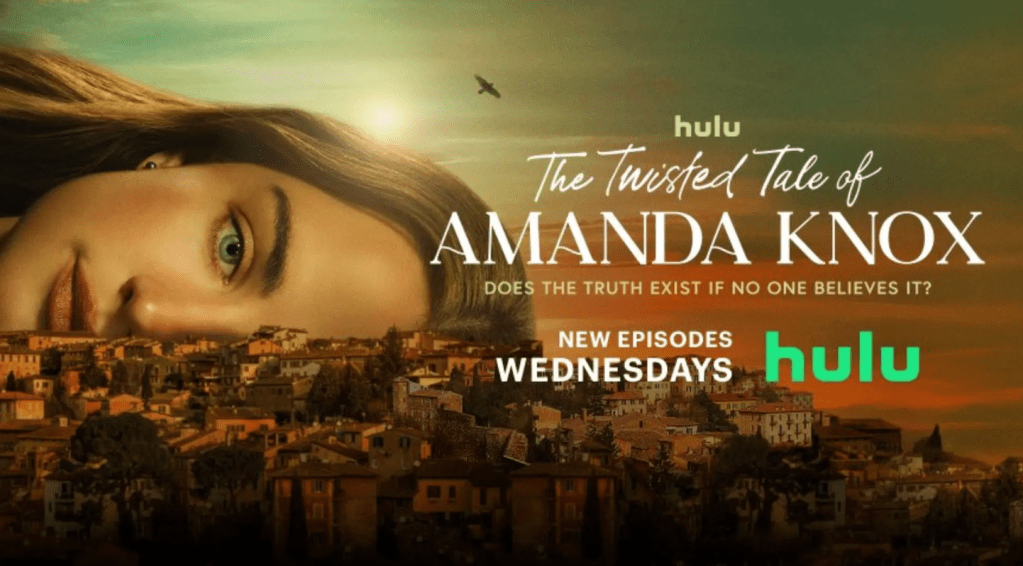

II. The Twisted Tale of Amanda Knox: Two Mothers, One Truth

Hulu’s The Twisted Tale of Amanda Knox (2025) retells one of the most controversial cases of the century with fresh eyes—and extraordinary restraint. Anna Van Patten delivers a stunning performance as Amanda Knox, balancing naivety and resilience in a role that demands both. But what impressed me most wasn’t the portrayal of Amanda herself—it was the humanity extended to everyone involved.

One of the most powerful scenes comes early in the series: Meredith Kercher’s mother walking into the morgue to identify her daughter’s body. It is filmed with such respect, such restraint, that the viewer feels grief without voyeurism. The camera doesn’t exploit the moment—it honors it. Later, we see Edda Mellas, Amanda’s mother, standing on the other side of that same abyss: a parent watching her child crumble under the weight of a false accusation. Two mothers, two daughters—both victims, both bound by the merciless machinery of a justice system desperate for answers.

The series succeeds precisely because it refuses to take shortcuts. It doesn’t turn pain into spectacle. It shows, instead, how a flawed investigation—pressured by media frenzy and public outrage—can spiral into moral disaster. Amanda Knox’s 2015 book Free: My Search for Meaning anchors the narrative. Yes, it’s subjective—of course it is—but every story deserves to be told from within. The producers, among them Monica Lewinsky, understand this too well. Lewinsky herself was publicly humiliated in the 1990s, tried in the court of public opinion, and left to carry a scar not unlike Amanda’s: a woman turned symbol, stripped of nuance.

There’s a chilling familiarity to that process. When we need someone to blame, we stop seeking truth. When a community demands justice at any cost, the price is often truth itself. That’s where the Hulu series triumphs—not just as entertainment, but as a quiet meditation on empathy and accountability. It asks: What if it were your daughter? What if you were the one behind bars?

The bridge from Amanda Knox to the broader conversation about justice is not difficult to cross. It naturally leads us to organizations like The Innocence Project, which works tirelessly to right such wrongs:

“The Innocence Project works to free the innocent, prevent wrongful convictions, and create fair, compassionate, and equitable systems of justice for everyone… We are committed to helping each person we represent rebuild their life post-release.”

The connection between Knox and this movement is clear. Her case reminds us that justice systems—whether in Italy, the United States, or anywhere—are only as reliable as the humans who run them. And humans, as we know, are fallible.

III. Reflections on Justice

Justice. Such a beautiful word—so absolute in theory, so fragile in practice. As I watched The Twisted Tale of Amanda Knox, I couldn’t help but think: what does it mean for justice to be served? Who decides when the scales are balanced?

In the Kercher case, it seemed that justice had to look like someone being punished—because an innocent girl was dead, and the public needed closure. But justice born out of fear or outrage is not justice at all. It is appeasement. It is theater.

And yet, I understand that need for closure. I am a father. I cannot begin to imagine the agony of Meredith’s parents. Still, if justice is administered by humans, and all humans are imperfect, then every conviction carries the shadow of potential error. If that conviction ends a life—through imprisonment, or worse, through execution—what do we do when the truth changes after the fact? That is my greatest fear: that justice, meant to uphold dignity, can become its opposite.

Sometimes I think justice should not be a sword but a mirror—something that reflects our collective humanity, rather than punishes it. But that’s idealistic, isn’t it? Because societies often confuse punishment with order, vengeance with peace. We call it “closure,” but closure doesn’t bring the dead back. It only silences our discomfort.

When the state kills a murderer, is that not also a killing? Does moral authority absolve the act itself? “Thou shalt not kill”—does that commandment have exceptions written in small print? And what if we discover, too late, that the person we executed was innocent?

We have seen this happen, again and again. In the United States, the list of posthumous exonerations is long enough to fill entire libraries. In Italy, in Spain, in Latin America—the same story repeats: someone pays for a crime they did not commit, simply because justice must be seen to be done.

That’s what frightens me the most—that justice has become a spectacle. A performance staged for public reassurance rather than truth. I think of Guccini’s Silvia again—locked away because she dared to think differently.

And I think of Amanda Knox—locked away because she was easy to misunderstand.

Justice should never depend on narrative convenience. It should depend on truth, however long it takes to find it. In the end, justice is not about winning a case; it is about preserving our humanity while we seek the truth. And that’s why stories like Amanda’s, Silvia’s, and countless others matter: they remind us that justice, when stripped of compassion, becomes just another form of cruelty.

Guccini closes Canzone per Silvia with a line that echoes through decades and borders:

“Che sempre l’ignoranza fa paura, ed il silenzio è uguale a morte.”

Because ignorance always breeds fear, and silence is equal to death.

Ignorance and silence—those are the true enemies of justice. And as long as we keep singing, writing, and questioning, we refuse to let them win.

(c) Francesc Borull, 2025