By Francesc Borrull · January 12, 2026

I. Introduction — Royalty Without a Crown

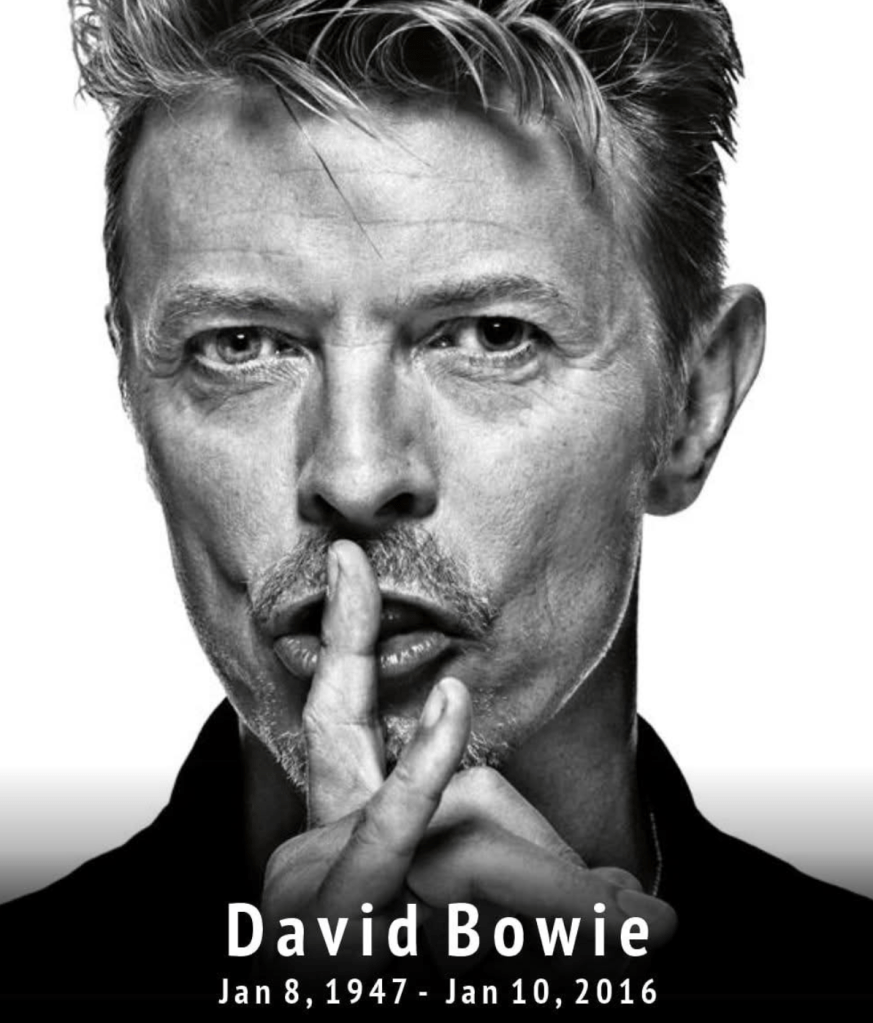

On January 10, 2016, the world lost David Bowie.

Ten years ago—exactly.

I am writing this not because grief follows calendars, but because distance matters. Distance allows the noise to recede, the reflexive tributes to quiet down, and memory to begin doing what it does best: separating admiration from understanding.

David Bowie was not simply a great musician. He was royalty—artistic royalty—in the fullest sense of the word. Not because he demanded reverence, but because he earned it through vision, discipline, curiosity, and risk. Popular music has many stars. It has very few monarchs.

My devotion to Bowie did not arrive all at once. It unfolded over years—sometimes decades—through records, images, interviews, silences, returns, and disappearances. Bowie was never something you “finished.” He was someone you grew into. And in doing so, you grew differently.

This entry is not an obituary. It is not an attempt at comprehensiveness. It is a tribute—ten years after his death—to an artist who redefined what popular music could hold: ambiguity, intellect, danger, tenderness, theatricality, and grace.

II. A Life in Motion: Persona, Ambiguity, Becoming

Summarizing David Bowie’s life in two or three paragraphs is, by definition, an act of reduction. But some truths endure even when compressed.

Born David Robert Jones in London in 1947, Bowie’s early years were marked by restlessness—musical, social, existential. Long before fame, he understood that identity was not something one discovered but something one constructed. This insight would become the axis of his entire career.

His androgynous persona and his public embrace of sexual ambiguity were not gimmicks, nor were they merely provocations. They were philosophical positions. Bowie refused the tyranny of fixed categories—male/female, straight/gay, authentic/artificial, rock/pop. He made ambiguity not only visible but beautiful, at a time when ambiguity was dangerous.

What set Bowie apart was not just reinvention, but intentional reinvention. Each transformation was rigorous, researched, and aesthetically coherent. He read constantly, listened widely, and absorbed art, fashion, theater, cinema, and literature—and then transmuted them into something unmistakably his own.

Bowie did not chase relevance. He interrogated it.

III. A Survey of Sound: The Eras of a Chameleon

If Bowie’s life was a question, his discography was a series of answers—each provisional, each brave.

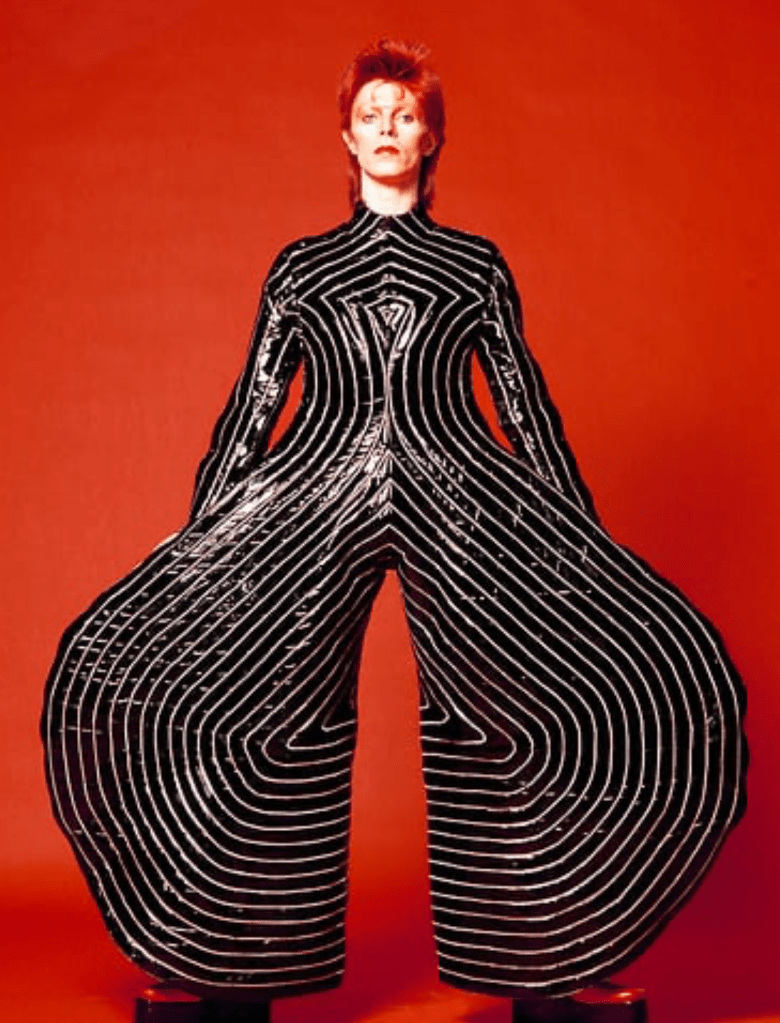

The Glam Revelation: Ziggy and the Early 70s

With The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, Bowie did something radical: he turned the rock album into a narrative mask. Ziggy was not a character in the theatrical sense; he was an idea—alienation, fame, apocalypse, desire. Glam rock became a vehicle for existential drama.

This period established Bowie as a cultural disruptor. Music, fashion, performance, and sexuality fused into a single statement: identity is mutable.

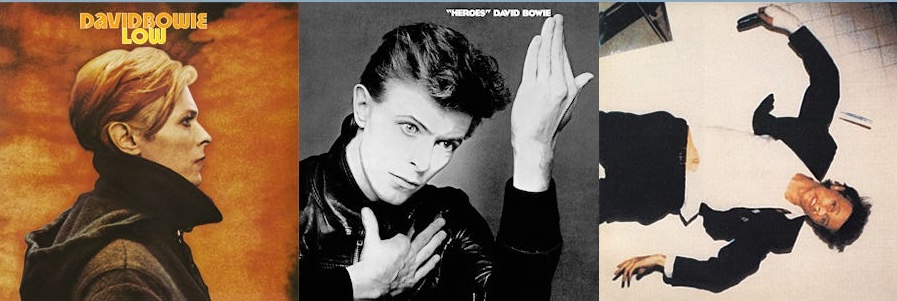

The Berlin Years: Art, Isolation, and Renewal

The so-called Berlin Trilogy (Low, “Heroes”, Lodger) marked a decisive turn inward. Fragmented, electronic, often instrumental, these records abandoned rock stardom for artistic survival. Bowie, newly sober, worked with Brian Eno not to innovate for innovation’s sake, but to rebuild himself through sound.

These albums remain some of the most influential in modern music—not because they were immediately accessible, but because they redefined what an artist at the peak of fame could risk.

Collaboration as Conversation: Bowie with Others

For all his singularity, David Bowie was never a closed artist. He understood collaboration not as dilution, but as conversation—a way of testing his ideas against other formidable voices.

Nowhere is this clearer than in Under Pressure, recorded with Freddie Mercury and Queen. What makes the song extraordinary is not merely the pairing of two titanic personalities, but the absence of ego in the final result. Neither Bowie nor Mercury dominates. Instead, the song unfolds as a tension—voices circling one another, yielding space, pushing back, listening. “Under Pressure” is not a showcase; it is a negotiation. And that, perhaps, is why it has endured.

But this was not an isolated moment. Bowie repeatedly placed himself in service of other artists at crucial points in their careers: writing and producing All the Young Dudes for Mott the Hoople; co-authoring and producing The Idiot and Lust for Life with Iggy Pop, effectively helping to rebuild his career; producing Transformer for Lou Reed; exchanging lines and energy with John Lennon on Fame; and even embracing cultural contrast in his duet with Bing Crosby on “Peace on Earth / The Little Drummer Boy.”

Bowie’s career is marked by such encounters: artists, producers, musicians drawn into his orbit not to be absorbed, but to be activated. These collaborations were not footnotes. They were evidence of an artist confident enough to share the center—and generous enough to step aside when the moment required it.

The 80s and Beyond: Success, Excess, Reassessment

The 1980s brought commercial triumph—and, at times, artistic compromise. Bowie himself would later critique this period. Yet even here, his instincts never fully dulled. He learned from success the way others learn from failure.

The 1990s and 2000s saw reinvention again: industrial textures, drum & bass experiments, a refusal to settle into legacy-act comfort. Bowie aged without nostalgia.

The Final Statement: Blackstar and “Lazarus”

Released just days before his death, Blackstar was not a farewell—it was a controlled detonation. Nowhere is this clearer than in “Lazarus”: the imagery, the lyrics, the video. Bowie knew he was dying. He chose art over sentimentality.

Few artists have choreographed their own disappearance with such clarity. Blackstar was released into the world as Bowie exited it, leaving behind not closure, but meaning.

IV. A Personal Curation: Ten Bowie Albums That Endure

Ranking David Bowie albums in a strict hierarchy feels beside the point. Bowie’s work resists ladders; it invites return. What matters, at least to me, is not which albums are “best,” but which ones continue to speak—those I come back to, and why.

What follows is not a canon, but a personal curation: my ten favorite David Bowie albums, presented in chronological order, that have remained alive for me over time.

Hunky Dory (1971)

This is where Bowie’s intelligence fully surfaces. Hunky Dory is literate, melodic, playful, and quietly radical. It announces an artist who understands that pop music can think without losing grace. Its songs feel light on the surface, but they are architecturally precise—and endlessly revisitable.

The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (1972)

This is not just the album that made Bowie famous; it is the album that made becoming a legitimate artistic act. Ziggy is myth, theater, apocalypse, and confession all at once. What continues to astonish is not the flamboyance, but the control: every song advances the character, the idea, the world. Few albums in popular music feel this fully inhabited.

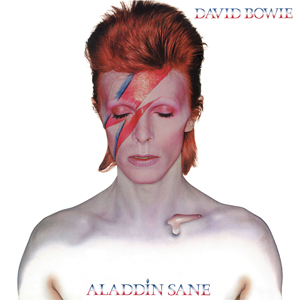

Aladdin Sane (1973)

Often misunderstood as a Ziggy sequel, Aladdin Sane is really the sound of fragmentation. It is sharper, more anxious, more unstable—glam rock cracking under the pressure of success and excess. The famous lightning bolt is not decoration; it’s a fracture line. This is Bowie learning that identity, once unleashed, has consequences.

Diamond Dogs (1974)

Diamond Dogs is Bowie at his most feral and theatrical, a world already beginning to decay as it is being built. Part dystopian fantasia, part glam-rock apocalypse, the album expands the Ziggy universe into something darker, more unstable, and more literary. Its loose Orwellian vision and jagged soundscape feel deliberately unfinished, as if collapse were part of the design. What endures is its ambition: Bowie pushing character, narrative, and performance beyond glam into something more dangerous and unsettling.

Station to Station (1976)

This is Bowie at a dangerous threshold. Station to Station stands between American soul and European austerity, between excess and erasure. The title track alone feels like a corridor leading toward the Berlin years. Cold, disciplined, and unsettling, it is one of his most powerful statements.

Low (1977)

Low is not an easy album, and that is precisely its virtue. Side A feels wounded and compressed; Side B drifts into instrumental desolation. This is Bowie stripping himself down to process, texture, and atmosphere. It rewards patience and maturity—and it continues to sound like the future, decades later.

“Heroes” (1977)

If Low is withdrawal, “Heroes” is confrontation. The title track has become iconic, but the album’s real power lies in its balance of urgency and restraint. It is political without slogans, emotional without sentimentality. Much of its nervous intensity comes from Robert Fripp’s guitar work—recorded in a single day—whose sustained, serrated lines cut through the songs like exposed wiring. Few records capture defiance so quietly—and so convincingly.

Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) (1980)

This is Bowie at his most balanced: experimental instincts sharpened by pop discipline. The songs are tight, nervous, and deeply strange beneath their surfaces. In many ways, this album feels like a summary of everything he had learned up to that point—without nostalgia, without retreat.

Reality (2003)

Reality reflects an artist at ease with himself. Direct, energetic, and unburdened by myth, it has a clarity that only comes after decades of reinvention. There is confidence here without arrogance—late-period Bowie without heaviness, and that is its virtue. The album was followed by the A Reality Tour release, which documents the tour that brought this material fully to life and stands as one of Bowie’s finest live statements. Generous, musically expansive, and deeply assured, it captures Bowie in full command—an artist revisiting his past without nostalgia, and performing squarely in the present tense. It is, quite simply, a late-period triumph.

Blackstar (2016)

Blackstar is not simply Bowie’s final album; it is a deliberate artistic leave-taking. Dense with symbolism, daring in sound, and unsparing in its themes, it transforms mortality into form. Knowing the context deepens its impact, but even without it, the album stands as a fearless act of creation at the edge of life.

These albums are not relics of a finished past. They remain active—changing as I change, revealing new contours with time. That, perhaps, is the surest sign of enduring art.

V. Beyond Music: Bowie’s Cultural Gravity

Bowie’s influence extends far beyond sound. He altered fashion by liberating it from gender—and by turning clothing into performance. He altered performance by turning the stage into a conceptual space. He altered popular culture by proving that intelligence and mass appeal are not opposites.

Most importantly, Bowie gave permission—to be different, to evolve, to contradict oneself without apology. For countless people, especially those who felt misaligned with the world as it was, Bowie was not just an artist. He was evidence that another way of being was possible.

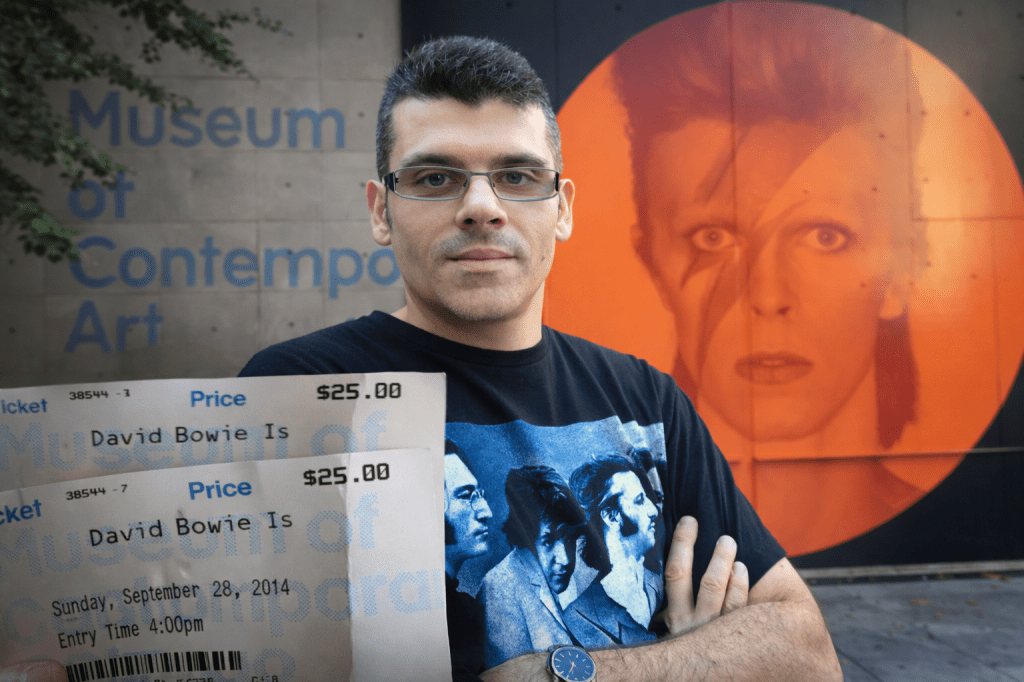

That understanding was crystallized for me in 2014, when I attended the David Bowie Is exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. The experience was overwhelming—not because of nostalgia, but because of coherence. Manuscripts, costumes, stage designs, videos, and sound were presented not as memorabilia, but as a single, integrated body of thought. Bowie emerged not simply as a musician who flirted with other disciplines, but as a fully realized visual and conceptual artist.

Walking through that exhibition made something unmistakably clear: Bowie did not merely influence culture. He occupied it—across music, fashion, theater, and art—with intention, rigor, and vision. Seeing his work framed in a museum context did not elevate it; it revealed what had been true all along.

VI. Conclusion — Ten Years Later, Still Ahead of Us

Ten years after his death, David Bowie does not feel past. He feels ahead.

His work has not aged into nostalgia; it has matured into reference. Each new generation encounters him not as history, but as possibility. That is the mark of true artistic royalty.

Bowie once said that aging is an extraordinary process where you become the person you always should have been. In death, he completed that process—not by disappearing, but by leaving behind a body of work that continues to ask questions we are still learning how to answer.

Ten years later, his absence is still felt.

And his presence—somehow—still grows.

© Francesc Borrull, 2026